“It’s hot. It’s hot! I feel the warm air in waves when someone walks past me.” A thought from the field notes in the first visit this summer to the Masca Theatre’s set warehouse, together with the students from the Recycling Workshop, held by the architect-scenographer Gabi Albu, within the Helix project for Masca – cultural and community center.

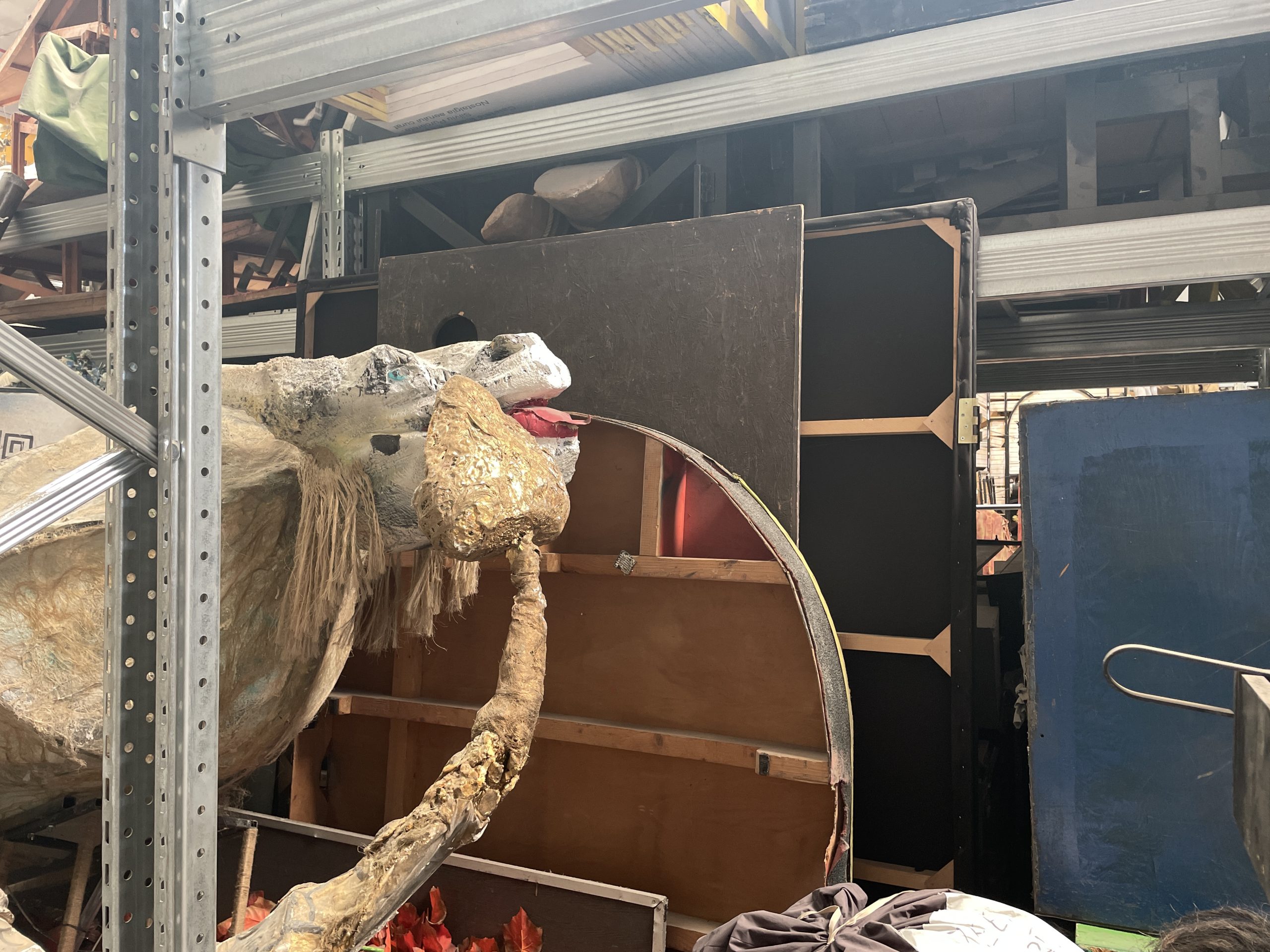

It’s a spacious hall with two rooms, one full of eyes, one empty. A bright and warm hall, so warm on these summer days. You can see the dust threads floating in waves among all the decorations stored here. In a quick tour, Adi and Vasile, Masca’s machinists for years, show us pieces whose form or function I don’t immediately make out but which are perfectly recognizable to them: “That’s from Servant to Two Masters …”, “look, there … these were in Living Statues”. This collage is mind-boggling for someone entering a theater warehouse for the first time.

But I realize I never really thought about it – where do they keep all those things you see on stage in a show? How heavy is a platform on which the scenery is mounted that creates the illusion of a separate space on an 80-square-foot stage? How does the upholstery of a sofa used in multiple performances feel? How easy is it, as an actor, to move around the furniture on stage, or to move it during a set change?

But here in the warehouse, all the objects are felt, tangible: their textures, their weight, their (un)functionality come to the fore and you find yourself imagining their multiple lives – from one performance to another and now to a new form and a different role in the Masca experiment. What does it mean to work with the existing set in this experiment to make the theater green?

What is green theater?

Much of the fascination of theater is the ephemerality of the art it shares with audiences. In practical terms, however, this means the materials and energy used to create each performance. Europe’s arts and cultural institutions are at different points in a complicated but necessary process of assessing how to manage and produce performances. An example of an already nuanced strategy, the National Theatre in London is proposing a three-pillar action model: production, buildings, processes. This model builds on the The Theatre Green Book (TGB), started by theater people in the UK in 2021 and now expanding to countries around the world.

In short, the National Theatre in London addresses the production pillar by monitoring material consumption and working to achieve 50% recycled/reused materials and 65% reusable materials at the end of a performance (these are the rates indicated as a baseline standard in the TGB). On the buildings side, the National Theatre London team is replacing electricity, water, and heating systems with low energy-consuming ones; at the same time, the Theatre’s buildings are being re-thought in terms of their connection to the natural environment, whether by creating terraces and flower beds on roofs and among buildings, planting, or building bird and insect nests. All these measures are complemented by the third pillar, the process pillar. In particular, the National Theatre in London is focusing on educating staff on sustainability, developing waste recycling operations to achieve at least 65% recycling, and creating food sourcing operations that focus on locally produced food, recycled/recyclable packaging and working with external companies to reduce food waste.

In Romania, Masca is taking the first steps towards an ecological and sustainable theater not only in terms of the use of materials but also in terms of the community gathered around the theater. The warehouse visit described above initiated this experiment with a 5-day Set Recycling Workshop. There were about 10 of us – Masca’s machinists, 5 students and recent graduates in scenography at UNARTE and UNATC – participants of the Recycling Workshop, Gabi Albu – architect-scenographer and workshop facilitator, me – anthropologist, and Maria Drăghici – artist and researcher focused on community art, who came to document the process. This is the first workshop in the series of the Helix project at Masca – cultural and community center, funded by AFCN. What are we all trying to do? The first steps in transforming Masca into an ecological theater and, further on, a center for the community in the neighborhood and in Bucharest.

What resources are needed for this transformation? Over the 5 days, spending 5-6 hours a day in the warehouse or in the theater with the students, the architect-scenographer, and the machinists, I discovered how the technical, conceptual, and affective dimensions of the process intertwine.

What we know and do, how we look, how we feel

Perhaps the practical, technical dimension is the first that comes to mind when thinking about a process of recycling decor. How to choose the objects, how to evaluate the materials from which they are made, how to decide in what way they could be reused. And, indeed, the first discussions and activities were just that; after a discussion with the students about what practical experience they already had (because “strictly from theory you know nothing”), Gabi gave them a summary of the situation of the theater warehouses in Bucharest and in the country, then emphasizing the technical aspects – if you learn how to dismantle a set, you learn even better how it works and what to ask from the theater workshop that builds your sets. In addition, and interestingly as a technical aspect, through dismantling and applied work with the object, you learn the language of the profession and develop professional relationships where you are recognized as a professional in your craft as a set designer.

But evaluating and working with sets in a sustainable process also means a change of perspective, a recognition and keeping in mind of the set as an object with multiple lives or, in technical terms, a modular object – in the way it is built and the way it is used. This shift in perspective has to be a deliberate effort, at least at the beginning of its approach to creating a sustainable production process, because it’s not an easy process – ” people prefer not to recycle because it’s more labor,” Gabi tells us. At the same time, set designers in Romania, especially those at the beginning of their careers, have a practice of reusing sets for a simple reason – necessity. New materials aren’t always available, budgets are often tight, so people get into the business by practicing reuse from the start.

What the Masca Recycling Workshop is trying to do in addition is to change the perspective so that the principle of the Masca Recycling Workshop is directed towards the future(how can I make a design with a high degree of reuse?), not just towards the past(how can I reuse existing decor?). All the more so, the Recycling Workshop is integrated with the Repurposing Workshop, where scriptwriters create sketches of urban furniture to be built and placed in connection with the Landscape Workshop, where participants will plant the Masca garden. In this way, the scriptwriters and the other workshop participants follow the trajectory of the set, from an object and a collection of materials, to their materialization into an object with a new role for the theatre and the community around the theatre.

Somewhat less visible, perhaps, is the affective dimension of these sets – the memories they bring up for the theater team, the pride of those who built them that they preserve, tangibly, in each joint. As I wander around the warehouse on one of the workshop days, trying to help, but seeing well that the students and Gabi are working precisely, already knowing each other’s moves, in a sufficient configuration, not needing an extra hand (a hand already busy taking notes), I am caught by Mihai, Masca’s technical director – “Let me show you a well-made set!”. We pass into the other room, organized by color through tall storage structures, and he shows me a circular platform, made of triangular segments of wood, which I have a hard time understanding why it is special.

“This one rotates!” he says and explains in a breath how versatile this set piece was. In another corner, Adi, one of the machinists, and I are looking with Adi at some rectangular platforms, very versatile in their turn because you can build different structures, depending on the needs of the show. Apparently nothing spectacular about such a platform, sort of a big but low wooden box. But Adi lifts it up and shows me underneath – a solid, carefully built structure that shows care for the object and its function in the show, these platforms being essential not only to give shape to the set, but also to keep the actors safe. However, these are also the objects we work with in the Recycling Workshop, precisely because of their versatility; through them, we also make and unmake the emotional connections that theater people, be they machinists, actors, set designers, have with the set. Embarking on this experiment to create an ecological theater requires attention to this dimension that we sometimes lose sight of.

In the weeks to come we, the project team, will share more about Helix at Masca here – discussions about the participatory design approach (the centerpiece of the project), stories about the trajectories of the decorative objects, multi-sensorial illustrations of different working processes, reports from the different workshops of Reconversion (Urban Furniture), of Landscape and Street Art. For the last two, you can still sign up at the attached links!

See you soon,

Alina

0 comments on “How many lives does a theater set have? Or how to lay the foundations for an eco-friendly neighborhood theater (by Alina Apostu)”